The word tattoo comes from the Tahitian word “tatu” meaning “to mark something”.

It can be claimed that the history of tattoos started around 12,000 BC. The purpose of tattooing has varied from culture to culture and era to era.

Tattoos have always played an important part in ritual and tradition. On Borneo, women tattooed symbols on their forearms to indicate skills. If a woman wore a symbol that indicated she was a skilled weaver, her status as prime marriageable material was increased.

Tattoos around the wrist and fingers were believed to ward away illness.

Throughout history, tattoos have been used to indicate membership within a clan or society. Even today groups like the Hell’s Angels traditionally get tattoos of their particular group symbol. Even on TV and in the movies, tattoos have been used to indicate membership in a secret society.

Traditionally, it has been believed that to wear an image calls to the wearer the spirit of that image. This idea still holds true today, as may be seen in the proliferation of tigers, snakes, and birds of prey in tattoo artwork.

The earliest tattoos in recorded history may be found in the Fertile Crescent ( Egypt ) during the time of the construction of the Great Pyramids, though they probably actually started much earlier. When the Egyptians expanded their empire, the tradition of tattooing spread as well. The surrounding civilizations of Crete, Greece, Persia, and Arabia picked up and expanded the art form. By 2000 BC the practice had spread all of the way into China.

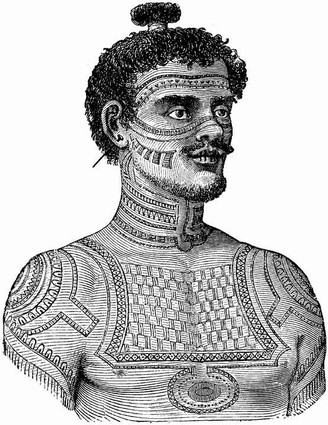

The Greeks used tattooing for communication amongst spies. Markings identified spies and showed their ranks. The Romans used tattoos to mark criminals and slaves; this practice is still carried on today in many places. The Ainu people of western Asia used tattooing to show social status. Girls coming of age were marked to announce their place in society, as were married women as well. The Ainu are noted for introducing tattoos to Japan where it developed into a religious and ceremonial rite. In Borneo, women were traditionally the tattooists. They produced designs indicating the owner’s station in life and to which tribe he belonged. Kayan women had delicate arm tattoos that resembled lacy gloves. Dayak warriors who had “taken a head” had a tattoo on their hand denoting it. These tattoos garnered respect and assured the owner’s status for life. Polynesians developed tattoos to mark tribal communities, families and even rank. They brought their art to New Zealand and developed a style of facial tattooing called Moko which is still being used today. There is evidence that even the Maya, Inca, and Aztecs used tattooing in their rituals. The art of tattooing also spread to isolated tribes in Alaska, the style indicating that it was learned from the Ainu.

In the west, early Britons used tattoos in ceremonies. The Danes, Norse, and Saxons tattooed family crests (a tradition still practiced today). In 787 AD, Pope Hadrian banned tattooing. It still thrived in Britain until the Norman Invasion of 1066. The Normans disdained tattooing. It disappeared from Western culture from the 12th to the 16th centuries.

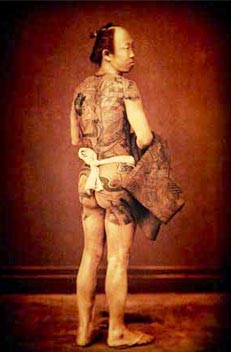

While tattooing diminished in the west, it thrived in Japan. At first, tattoos were used to mark criminals. First offenses were marked with a line across the forehead. A second crime was marked by adding an arch. A third offense was marked by another line. Together these marks formed the Japanese character for “dog”. It appears this was the original “Three strikes your out” law. In time, the Japanese escalated the tattoo to an aesthetic art form. The Japanese body suit originated around 1700 as a reaction to strict laws concerning conspicuous consumption. Only royalty was allowed to wear ornate clothing. As a result of this, the middle class adorned themselves with elaborate full-body tattoos. A highly tattooed person wearing only a loin cloth was considered well dressed, but only in the privacy of their own home.

While tattooing diminished in the west, it thrived in Japan. At first, tattoos were used to mark criminals. First offenses were marked with a line across the forehead. A second crime was marked by adding an arch. A third offense was marked by another line. Together these marks formed the Japanese character for “dog”. It appears this was the original “Three strikes your out” law. In time, the Japanese escalated the tattoo to an aesthetic art form. The Japanese body suit originated around 1700 as a reaction to strict laws concerning conspicuous consumption. Only royalty was allowed to wear ornate clothing. As a result of this, the middle class adorned themselves with elaborate full-body tattoos. A highly tattooed person wearing only a loin cloth was considered well dressed, but only in the privacy of their own home.

William Dampher is responsible for re-introducing tattooing to the west. He was a sailor and explorer who traveled the South Seas. In 1691 he brought to London a heavily tattooed Polynesian named Prince Giolo, Known as the Painted Prince. He was put on exhibition, a money making attraction, and became the rage of London. It had been 600 years since tattoos had been seen in Europe and it would be another 100 years before tattooing would make it mark in the West.

In the late 1700s, Captain Cook made several trips to the South Pacific. The people of London welcomed his stories and were anxious to see the art and artifacts he brought back. Returning form one of this trips, he brought a heavily tattooed Polynesian named Omai. He was a sensation in London. Soon, the upper-class were getting small tattoos in discreet places. For a short time tattooing became a fad.

What kept tattooing from becoming more widespread was its slow and painstaking procedure. Each puncture of the skin was done by hand the ink was applied. In 1891, Samuel O’Riely patented the first electric tattooing machine. It was based on Edison ‘s electric pen which punctured paper with a needlepoint. The basic design with moving coils, a tube, and a needle bar, are the components of today’s tattoo gun. The electric tattoo machine allowed anyone to obtain a reasonably priced and readily available tattoo. As the average person could easily get a tattoo, the upper classes turned away from it.

By the turn of the century, tattooing had lost a great deal of credibility. Tattooists worked the sleazier sections of town. Heavily tattooed people traveled with circuses and “freak Shows.” Betty Brodbent traveled with Ringling Brothers Circus in the 1930s and was a star attraction for years.

The cultural view of tattooing was so poor for most of the century that tattooing went underground. Few were accepted into the secret society of artists and there were no schools to study the craft. There were no magazines or associations. Tattoo suppliers rarely advertised their products. One had to learn through the scuttlebutt where to go and who to see for quality tattoos.

The cultural view of tattooing was so poor for most of the century that tattooing went underground. Few were accepted into the secret society of artists and there were no schools to study the craft. There were no magazines or associations. Tattoo suppliers rarely advertised their products. One had to learn through the scuttlebutt where to go and who to see for quality tattoos.

The birthplace of the American style tattoo was Chatham Square in New York City. At the turn of the century it was a seaport and entertainment center attracting working-class people with money. Samuel O’Riely came from Boston and set up shop there. He took on an apprentice named Charlie Wagner. After O’Reily’s death in 1908, Wagner opened a supply business with Lew Alberts. Alberts had trained as a wallpaper designer and he transferred those skills to the design of tattoos. He is noted for redesigning a large portion of early tattoo flash art.

While tattooing was declining in popularity across the country, in Chatham Square in flourished. Husbands tattooed their wives with examples of their best work. They played the role of walking advertisements for their husbands’ work. At this time, cosmetic tattooing became popular, blush for cheeks, colored lips, and eyeliner. With World War I, the flash art images changed to those of bravery and wartime icons.

In the 1920s, with prohibition and then the depression, Chatham Square lost its appeal. The center for tattoo art moved to Coney Island. Across the country, tattooists opened shops in areas that would support them, namely cities with military bases close by, particularly naval bases. Tattoos were known as travel markers. You could tell where a person had been by their tattoos.

After World War II, tattoos became further denigrated by their associations with Marlon Brando type bikers and Juvenile delinquents. Tattooing had little respect in American culture. Then, in 1961 there was an outbreak of hepatitis and tattooing was sent reeling on its heels.

Though most tattoo shops had sterilization machines, few used them. Newspapers reported stories of blood poisoning, hepatitis, and other diseases. The general population held tattoo parlors in disrepute. At first, the New York City government gave the tattoos an opportunity to form an association and self- regulate, but tattooists are independent and they were not able to organize themselves. A health code violation went into effect and the tattoo shops at Times Square and Coney Island were shut down. For a time, it was difficult to get a tattoo in New York. It was illegal and tattoos had a terrible reputation. Few people wanted a tattoo. The better shops moved to Philadelphia and New Jersey where it was still legal.

In the late 1960s, the attitude towards tattooing changed. Much credit can be given to Lyle Tuttle. He is a handsome, charming, interesting and knows how to use the media. He tattooed celebrities, particularly women. Magazines and television went to Lyle to get information about this ancient art form.

Today, tattooing is making a strong comeback. It is more popular and accepted than it has ever been. All classes of people seek the best tattoo artists. This rise in popularity has placed tattooists in the category of “fine artist”. The tattooist has garnered a respect not seen for over 100 years. Current artists combine the tradition of tattooing with their personal style creating unique and phenomenal body art. With the addition of new inks, tattooing has certainly reached a new plateau.